[category science-report]

Mars Desert Research Station

End Mission Research Report

Crew 326 – Gaia

Dec 28th, 2025 – Jan 10th, 2026

Crew Members:

Commander Keegan Chavez

Crew Scientist: Benjamin Huber

Crew Engineer: Idris Stevenson

Health and Safety Officer: Katharina Guth

Green Hab Officer: Vindhya Ganti

Crew Journalist: Daria Bardus

Crew Biologist: Armand Destin

Mission Plan:

Crew 326 performed various research tasks, including engineering projects on RF communications, autonomous rover sample collection and navigation, in-situ resource utilization, environmental sensing. All 6 projects required Extra Vehicular Activities (EVA), thus adding realistic difficulties to the task. All projects had adequate time to perform research tasks, including gathering data, analyzing data, updating procedures, and drawing preliminary conclusions. The details of those reports will follow.

Relevant sections include research objectives and hypotheses, methods and experimental setup, data collected and observations, preliminary results and analysis, limitations of the analog environment, and recommendations for future MDRS crews.

1.

Title: Autonomous Mars Rover for Geological Sample Collection

Author(s): Vindhya Ganti

Objectives: Train an image-based navigation system on local landmarks to allow a rover to navigate autonomously.

Methods and Experimental Setup: To make the rover autonomous, first the rover needs to be able to identify different locations and have some sort of mapping system to identify where it is relative to other locations. To accomplish this task, a teachable machine learning image algorithm was fed roughly 20–35 images of three different locations (Hab, White Rock Canyon, and Kissing Camel) from various angles. Furthermore, some unlabeled images, or images that didn’t fit any of those three categories, were mixed into the dataset. Then, for preprocessing, the images were rotated +/- 15 degrees, converted to black and white, and morphed with the noise filter. Ultimately, this step was to build tolerance so that in conditions like low lighting and dust, the dataset could still identify the region correctly. 150+ images were created from the original 20–35. Then, annotations were assigned per image, identifying the different types into classes (Kissing Camel, White Rock Canyon, Hab, Unlabeled). In each class, images were assigned into three different types: train, valid, and test. Images in the train section would be used to teach the model, images in the valid section would be used to give feedback to the model for reiteration, and images in the test section would be completely new to the model, thus used to evaluate how accurate the model is.

The train_model.py file imports YOLO into the model, determining the number of epochs (iterations) the model goes through to train. The run_webcam.py file harnesses either the device’s webcam or an externally attached webcam. Once pointed at the location, the program will visibly box the rock structure, printing the label. After the user clicks “c”, the program closes the webcam, printing out the distance from the HAB.

Preliminary Results and Analysis: the model differentiates between the Kissing Camel region (both east and west ridges) and the HAB with 92.76% accuracy, calculated from the test type. Additionally, the model is differentiates between random photos of other regions and both of the locations. Further implementation of the code with White Rock Canyon is expected to occur after sim, since data collection occurred during Sol 12.

Recommendations: It would be ideal to connect imaging logic with the hardware of the rover. This means using the correct label and distance from the HAB, and then having the rover have a camera setup to autonomously move in the direction of the HAB.

Figure 1: Test Image vs Trained Image with Preprocessed Variations

2.

Title: Dust Storm Detection

Author(s): Idris Stevenson

Research Objectives: This study will investigate the discrepancies between different environmental metrics in various locations around a research base for the purpose of increasing the body of data with which researchers plan and execute research expeditions.

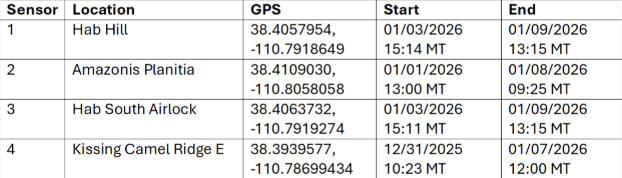

Methods and Experimental Setup: This study used a suite of sensors measuring temperature (C), pressure (Pa), humidity (%), and light (lux) alongside a Raspberry Pi to remotely log environmental metrics in a variety of locations. Sensors were placed around the Mars Desert Research Station in the locations enumerated in the table below to gather a variety of data points.

Preliminary Results:

Table 1: Sensor Location and Time in Environment

The data collected from the humidity and pressure sensors returned as expected. However, in some cases the measured light level was 0 during several daytime readings and the temperatures exceeded 30C at times.

Recommendations: Further data analysis planned to determine the measured differences between simultaneous readings on sensors at different locations and to evaluate the resulting usefulness of distributed environmental sensing.

The data returned and the manner of data retrieval opens additional considerations for future investigation. All data was stored locally and required manual download after collection, but the data collected is more useful if available in real time or remotely. In future investigation, the integration of LoRaWAN (Long-Range Wireless Area Network) into the system would enable remote accessing and data collection.

The sensors themselves also call for revision in design. Wind speed is a consideration for EVA planning at MDRS; because wind speed is not measured in the existing design, a mechanism for measuring wind speed is desired. Additionally, placing redundant sensors in the same enclosure could provide more accurate results than a single point for each location. Some mechanisms on the existing sensor suite could also be removed, as the current system measures gyroscopic, acceleration, and proximity data that is not desired. However, in the future, the acceleration data could be used to validate sensor stability, as one of the four sensor systems was discovered to be inverted upon collection.

The enclosure for the sensors is another system in need of development. The data collected indicates that the temperature in the enclosures exceeded 30C at times, far above the highest recorded temperatures at the location of interest, despite the enclosure opening the system to the surroundings. This means that the existing “deli-container” containment system may have provided a greenhouse effect that impacted the data.

The scope of this project would also be beneficial if it were scaled up in time and in size. Increasing the number of sensors and the time for which sensor data for each system overlaps with those in other locations would provide more valuable insight concerning the variability in environmental factors throughout testing.

3.

Title: Utilization of In-Situ Materials for Construction

Author(s): Benjamin Huber

Objectives: Gather materials from the surface of Mars to make bricks for construction and testing the strength of those bricks

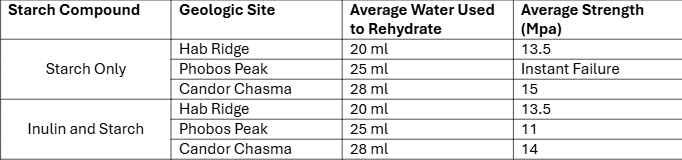

Methods and Experimental Setup: To complete the objective, small starch based concrete samples out of regolith from the MDRS region. In total, 4 brick samples were created for each geologic location, allocating two bricks for each brick type. One brick compound uses potato starch as a binder and the other compound uses potato starch and Jerusalem Artichoke inulin mixture (6 g of starch, 2g of inulin). These bricks were then strength tested using a rebound hammer. The general method of creating the bricks involves homogenizing the geologic samples and mixing them with the respective compounds. Then activate the starch in the lab oven. There is then a cooling and drying process before the samples are homogenized again and more water is added. Finaly the bricks are compressed. Then the bricks are dehydrated before testing with a rebound hammer.

Description, activities, and results: The first location that was chosen was along Hab Ridge Road (figure 1). This clay was chosen due to its dark red coloration indicating the presence of hematite. With this sample in the inulin and starch mix there were small starch granules that clumped together and hardened. After the dehydration and drying process, the bricks were significantly cracked and still moist in the center, which resulted in the bricks being able to only withstand three tests until failure. The next sample was red clay taken from near the peak of Phobos Peak (figure 1). During homogenization the clay did not mix well with the water and became sticky. After the bricks were formed and dehydrated, the outside had small cracking and salt had settled on the surface of the bricks. The Phobos Peak bricks stuck to the surface of the mold, which resulted in weakening prior to the final dehydration step. After multiple tests, the bricks were more cracked and significantly weakened and ultimately failed after 3 strength tests. The final samples, collected from Candor Chasma (figure 1), consisted of a sandy streambed material from halfway into the chasm. This sample had no cracking, but the rebound hammer made large indentations at the test site.

Table 2: Bricks Strengths and Water Used

Figure 2: Locations of Geologic Sample Collection

There were some difficulties with this research while at MDRS. Both dehydration steps had to be increased in duration. The first heating step changed from one hour to one hour and thirty minutes, and the final dehydration period had to be extended to leave the bricks out overnight at room temperature after the 4 hours of time to dry. The final dehydration period had to be done on a different day due to the power limitations of solar power; this could have weakened the bricks further (not dry enough). The sand brick is seen to be the preferable choice as it has the highest strength values for both compounds as well as no cracking when drying (this made it so the bricks did not fail after the third strength test). In the future I plan to make a 60% sand and 40% clay brick.

4.

Title: Terrain-Dependent RF Signal Propagation Mapping

Author(s): Katharina Guth

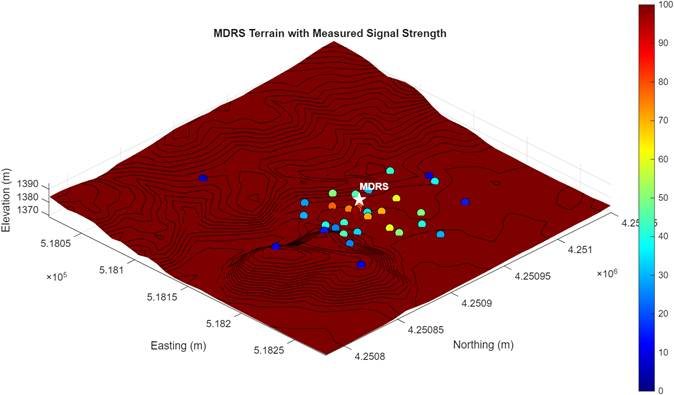

Research Objectives: The purpose of this research was to analyze radio frequency (RF) signal propagation in relation to terrain and radio frequency during EVAs at the MDRS site. Understanding RF propagation is critical for maintaining reliable communication, ensuring crew safety, and optimizing repeater placement for long-range communication. This study aimed to identify areas of signal attenuation, evaluate line-of-sight and elevation effects, and create terrain-dependent propagation maps for operational planning.

Methods and Experimental Setup: Five EVAs were conducted which provided RF data. During each EVA, the SS11 RF Field Strength Meter, equipped with an SMA male telescopic antenna, was used to measure relative RF field intensity. Antenna length was adjusted based on the quarter-wave calculation for the transmitted frequencies. GPS coordinates, including longitude, latitude, and elevation, were recorded simultaneously using a Garmin GPSMap64.

The HAB crew transmitted RF signals for one-minute durations on two channels: 152.375 MHz (Channel 1, long-range with the repeater) and ~162.995 MHz (Channel 3, local HAB base communication). Video recordings of the RF meter were captured during EVAs to allow post-mission extraction of signal strength data. Time stamps allowed alignment of GPS positions with RF readings, enabling spatial correlation between terrain features and signal behavior.

Data Collected and Observations: The dataset included the following: longitude, latitude, elevation, time, date, and signal strength. Data were collected across latitude 38.4051–38.4075 N and longitude 110.7935–110.7907 W and mapped across five regions: (1) MDRS Base, (2) Phobos Peak, (3) Candor Chasma, (4) Kissing Camel Ridge, and (5) White Rock Canyon.

Measurements at the MDRS Base used Channel 3, while other locations used Channel 1 for long-range communication. Strong signals were consistently observed near the HAB, in line-of-sight locations, and at elevated surfaces. A notable signal spike occurred at the base of Phobos Peak. Areas exhibiting signal attenuation included Candor Chasma, south of Kissing Camel Ridge, and within White Rock Canyon, although limited signal was readable.

Instances were observed where the EVA crew could hear the HAB base, but the base could not receive the EVA crew’s transmissions, likely due to the repeater placement favoring signals toward the base.

Preliminary Results and Analysis: Preliminary mapping indicates a clear correlation between proximity and elevation and signal strength, with terrain obstructions significantly reducing propagation. Line-of-sight dominance was evident, and signal degradation patterns were region-dependent. These initial findings suggest that careful consideration of topography is essential when planning repeater placement and EVA routes. The image below depicts the signal strength close to the HAB demonstrating how proximity indicates strong communication.

Figure 3: RF Signal Strength at MDRS Base

Limitations: The RF Field Strength Meter measured only relative intensity, requiring baseline readings for comparison. The meter also occasionally displayed irregular readings when gain was maximized, which was accounted for during post-processing. Additionally, initial attempts to use an RF Signal Generator were abandoned due to safety concerns. Sampling frequency and manual data extraction from video recordings also introduced further limitations in temporal resolution.

Recommendations: The terrain-dependent RF propagation maps generated in this study offer a valuable reference for EVA planning and informed repeater placement. Future research would benefit from using a calibrated RF meter capable of measuring absolute field strength, implementing automated data logging to improve temporal resolution, and expanding sampling in terrain-obstructed areas to more accurately quantify signal attenuation. Incorporating these findings into EVA planning will allow crews to anticipate potential communication drops, adjust travel routes or timing accordingly, and ensure the safety of analog astronauts during field operations.

5.

Title: Crew-Centric Interface for Performance Optimization at MDRS

Author(s): Armand Destin

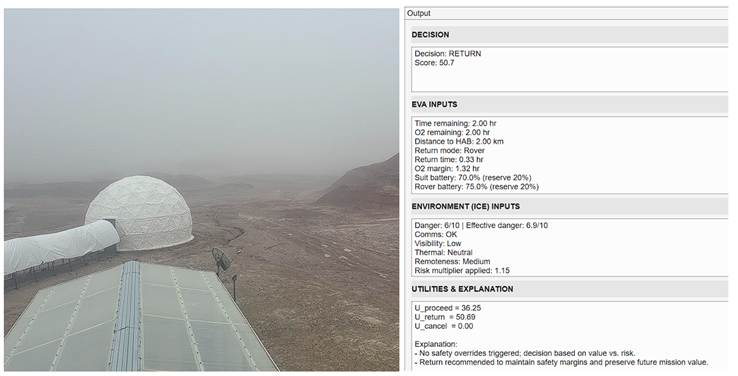

Research Objectives: Isolated, confined, and extreme environments (ICE) provide the groundwork to evaluate human interpersonal and human-machine interactions. These conditions come with the challenge of combating how to face challenges and choosing the best option that prioritizes the safety of crew members. As the space exploration community aspires to venture to Mars, resilience training, a conglomeration of data, and awareness of strenuous environments can be a critical starting point for these pursuits. This project developed a decision-making interface that assesses risk to inform analog astronaut crews of how to handle potential challenging and emergency situations. This project investigates the operations and responses of the environmental conditions and analog astronauts.

Methods and Experimental Setup: During the mission, several libraries of environmental observations were collected to inform the system of the expectations and assumptions that can be made to make scenarios that reflect the possibilities of occurrences on Mars. These libraries included weather, visibility, temperature, terrain, landforms, and distance. On extravehicular activities (EVAs), these observations and variations in the scenario were recorded in addition to the main mission objectives of that EVA. After completion and return of the EVA, the observations made on EVA were simulated in a minor iteration of the decision-making interface using MATLAB to provide a preliminary analysis of the conditions and the best option of choice for the crew, including either (1) proceed with the EVA, (2) return later, or (3) cancel the EVA. The library of observations creates several distinct scenarios to work with, including conditions like extreme fog, potholes in terrain, shorter EVA durations, wet terrain, and several geologic features (canyons, riverbeds, steep descents). The system’s behavior worked effectively, providing recommended action and associated score as well as rationale. The system includes multipliers that represent the realism of maximizing safety and minimizing risk. The collected observations offer robustness for uncertainty for situations that can arise in a Martian environment.

After the mission, further research will include incorporating human judgment data to compare with the system’s outputs. The crew members, now all with analog experience and exposure to ICE conditions, would be provided with a scenario and would provide a rating of whether to proceed, return, or cancel the EVA. Additionally, each crew member would provide their rationale as to why they gave that rating an option. Hypothetical scenarios will be based on the recorded environmental observations made from the mission.

Data Collected and Observations: Overall, the decision-support system was evaluated using manually defined environmental EVA scenarios. The resulting recommendations and utility values were logged and analyzed. No data was collected from or about individual crew members, and no system outputs were used to guide real EVA decisions. Future work for this project can include human input and comparison. It is recommended that the official system balance the effect of the risk multipliers to reflect the Martian environment, but not underscore danger or the effects of time. Additionally, the objectives originally proposed can be expanded to demonstrate the vastness of work and research that can be conducted during EVAs. The mission and the research project demonstrated the importance of resilience training and unity of effort amongst crews, and individually to be safe and support the mission.

Figure 4: Example Use Case of System Output

6.

Title: Autonomous Mars Rover for Geological Sample Collection

Author(s): Daria Bardus

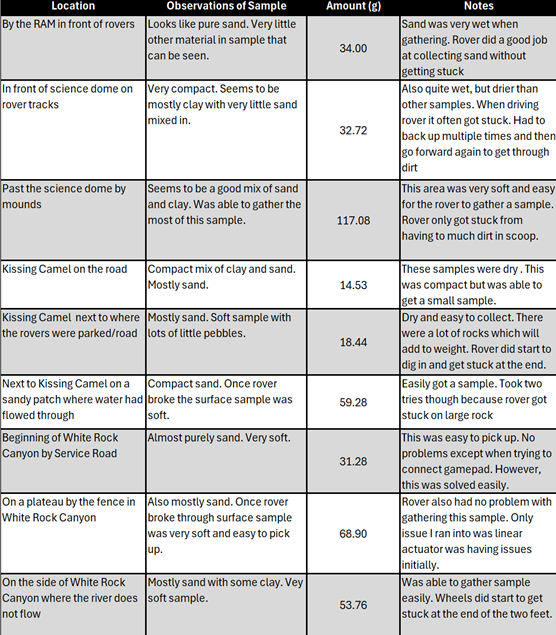

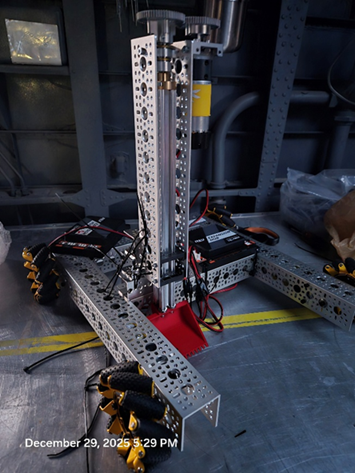

Research Objectives: The preliminary testing involved creating a rover that could be maneuvered with a joystick controller to collect a sample for later measurement and observation using a basic static scoop mechanism.

Methods and Experimental Setup: In total, three soil samples were collected from different areas around the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS), including Kissing Camel Ridge, White Rock Canyon, and the area immediately outside the HAB.

At each location the first step was to look for flat areas and try to find places with different types of soil to test the rover’s ability to collect varied samples. Then the rover was taken to the first location and set down.

A two-foot collection zone was measured and marked in front of the rover. The driver station was then used to start the program, and the joystick controller was used to first lower the scoop on the linear actuator and then drive the rover forward. When the rover got stuck the rover would then be directed to move backwards then forwards again and the scoop’s position was adjusted. When the rover had traveled approximately two feet, the scoop was raised and the sample was then placed into a bag for later measurement and observation.

Data Collected and Observations: Samples enumerated in the table below were used to quantify the performance of the rover.

Table 3: Sample Observations and Amounts (g)

Preliminary Results and Analysis: On average the rover was able to collect a sample of 47.78 g, which is considered a success because that fills approximately 42.56% of the scoop. During testing hard compact soils were difficult to collect due to the scoop not being able to break through the surface without getting stuck. Conversely, the wheels would dig into the soil if it was too soft. This could be fixed by adjusting the power of the motors in the drive train to help avoid the rover digging into the soil.

Limitations During this research it was found that the rover required four-wheel drive to easily collect a sample. Initially, front-wheel drive was used, but the rover would often get stuck when the soil was soft. It was also found that it was hard to fix connection issues while out on EVA. This is because EVA gloves made it hard to look at the setting on the phones used for the driver station and robot controller when there were connection issues. Lastly, it was found that testing on an inclined surface was complicated with the current setup of the rover. This was because simultaneous movement of the drivetrain and linear actuator was hard to achieve in a manual setup.

Recommendations: The next steps would include creating a new collection system and making the rover autonomous. In the current iteration of the rover, the scoop is made of 3D printed PLA+, but changing the material to something stronger would help with collection and would also help the rover overcome obstacles like rocks and not get stuck as often. Also, increasing the size of the scoop would allow the rover to collect more soil. Overall, this rover was able to demonstrate the possibility of making a small autonomous rover that can traverse Mars terrain and collect geological samples. A collection system that is not static and could store the sample in the rover would improve the feasibility of this project. Ideally a conveyor belt system would be used. Also, creating a navigation software would greatly improve the autonomy of the rover.

You must be logged in to post a comment.